East Coast vs. West Coast: The Odio Brothers' Story in the Washington Business Journal

Brothers Daniel and Sam Odio say D.C. doesn't sate entrepreneurial needs

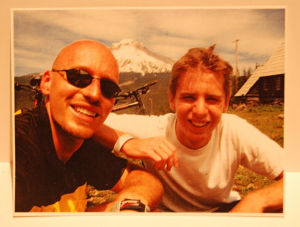

Herndon natives Daniel and Sam Odio share a last name, two alma maters and a gene for entrepreneurial risk-taking. Each brother has created a well-known, successful tech startup , mobile app builder PointAbout Inc. for Daniel, picture-sharing company Divvyshot for Sam.

But only one Odio brother stayed in D.C. Sam left in 2009 for a sunnier West Coast startup climate.

Sam's success out West, however, now has Daniel on the verge of following his younger brother to California: His company PointAbout , though still headquartered in D.C. , is putting down Western roots as well.

The Odios' story is a case study on why so many tech entrepreneurs journey westward to build companies, instead of staying in Washington or other East Coast tech hubs.

For most of his life, 25-year-old Sam walked a path cut by a brother nine years his senior. As a kid, big brother Daniel sold sodas from PriceClub to construction workers at 50 cents a pop; Sam did the same for Fourth of July crowds. Daniel fixed windows in the neighborhood; Sam fixed computers.

Now, 34-year-old Daniel for the first time finds himself shadowing his younger brother. Sam in early 2009 decamped from Virginia to enroll in Y Combinator, a Mountain View, Calif.-based seed fund and mentoring program, which helped him build Divvyshot into an attractive enough acquisition target for Facebook. The social media giant, where Sam now works, bought Divvyshot for an undisclosed sum in April , just a year and four months after the startup's launch.

With the same spirit, PointAbout recently opened a San Francisco office to develop its marquee product , AppMakr, a web-based program that lets non-developers build custom smartphone apps. PointAbout launched AppMakr in January, a year and a half after Daniel and three friends created the company as a software consulting firm in D.C.

Their new offering had significant buzz and big-name techie fans the likes of Guy Kawasaki and Seth Godin. What it didn't have was venture capital. Instead, the expansion was funded mostly by the co-founders' savings and PointAbout's consulting fees.

In D.C. , where Daniel originally sought venture funding for PointAbout and AppMakr , the process of raising capital "was like pushing a piece of rope uphill," he said. Within two months of opening a San Francisco office, Daniel is closing on a $1 million round from Bay Area investors.

Investors in the Washington area, he said, wanted too much of the company in exchange for funding. The differences don't stop there. The two brothers see a wide gulf in venture capital mentalities, the pool of available talent and even fashion choices: Nobody wears a suit to California startup events.

"It's a very different environment out here," Daniel said by phone from California, where he now spends much of his time. "I think it's a real shame. I wish D.C. would cater more to entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial activity, but it simply does not." Lest this sound like an extended assault on D.C.: The Odios are quick to mention that D.C. has its strengths , federal contracting and consulting, to name two of the biggest.

The Odios seem to have a genetic predisposition to entrepreneurship, stretching back for generations. Their great uncle owned a chocolate factory in Costa Rica, which he sold to Nestle. But their dad, a lawyer who immigrated from the tiny Central American nation in his 20s, had a more traditional path in mind for his two sons. "Our dad had a bit of an immigrant mentality," said Daniel. "Success equals having a really great job at a corporation."

The elder brother took that advice , at least at first. After graduating from the University of Virginia, he took a job with General Electric, spending a year and a half opening GE offices in Brazil and Argentina (he speaks both Spanish and Portuguese). The experience told him he didn't want to spend his life working for a big company. Instead, everything Daniel does is done with an entrepreneurial bent. During the real estate bubble, he leapt into residential sales, but did so as an independent broker under DROdio Real Estate Inc., using his own software to create unique search engines to attract clients.

Daniel's GE experience helped Sam avoid the corporate ladder altogether; instead, he went into business for himself before graduating from the University of Virginia. In Charlottesville, he started a currency exchange business that paid for school and gave him a little capital for Divvyshot's early days. Still, Sam never harbored serious hopes of building a successful tech startup on this coast. When it was time to get Divvyshot off the ground, "We had decided pretty early on that we would do everything we could to make it out West," he said. For Sam, Y Combinator was reason enough. The combination of critical mentorship for tech entrepreneurs and professional connections just doesn't have a clear parallel in the Washington area, he said.

Y Combinator led Sam to have dinner with Google software developer Paul Buchheit, the creator of Gmail. And it probably played a part in the startup's recent acquisition by Facebook, where Sam now leads a team driving advances in facial recognition software.

Picking on the Washington-area tech scene is, perhaps, unfair. No other area of the country looks competitive when held up to Silicon Valley. The region is anchored by Google, Apple and Facebook, as well as countless other tech companies. And Silicon Valley utterly dwarfs every other region in the nation in terms of the venture capital flowing to startups. In the second quarter, venture capitalists doled out $1.3 billion to Valley startups, accounting for half the value of all funding deals in the nation during that period, according to a recent report from PricewaterhouseCoopers. The Washington area came in fifth, at less than $200 million.

"I think there is an entire machine out here that has its roots in the 1950s," said Daniel. "It's that taking risk is seen as a positive thing, and that it leads to some giant positive outcomes. Whereas I think in D.C. , there is not a need to take risk."

What Silicon Valley has over D.C. - as well as New York and Boston , is scale, said John Backus of Reston-based early stage fund New Atlantic Ventures. But Backus, a Stanford graduate, said that doesn't mean this area is afraid of risk. New Atlantic Ventures, he said, has made seven first-time investments in startups over the past nine months, several of which had no revenue. "Clearly, we're taking a risk," Backus said.

Sam described what he calls Washington's "vicious cycle." There are fewer engineers to staff Washington-area startups, because most of them are working for titans like Facebook and Google. Without that crop of engineers, you have fewer investors. With less investment, you have fewer entrepreneurs.

The differences extend into California's extensive community of angels , investors who offer cash at an earlier stage than VCs and don't manage big funds of other people's money. D.C. could benefit from something like Angelist, a San Francisco-based network of angel investors who vet startups and match them with seed investments.

And Daniel points to one D.C.-based idea that showed promise a decade ago, but collapsed after the tech bubble burst: the Netpreneur Exchange. Netpreneur, founded by software entrepreneur Mario Morino, had helped organize the startup community and brought in speakers like Netscape co-founder Marc Andreessen. Daniel said he wanted to see the group make a comeback , or see a trade group pick up where it left off

"These West Coast luminaries are not going to come to the East Coast for fun," he said. "Some of them might, but many of them are perfectly happy being on the West Coast and innovating."